--NREL--tojpeg_1573570696415_x2.jpg)

In December 2015, 195 states signed up to the Paris Agreement. This is the most important pact for international cooperation on tackling climate change, and countries are taking steps to deliver on it. The UK, Norway, France and New Zealand are some of the countries that have legally committed to reach net zero emissions by 2050. But are countries actually on track to achieve the Paris Agreement targets?

This section explains how the Paris Agreement works and why COP26 in Glasgow, UK, is the time the nations of the world are next expected to step up their ambition levels. It also looks at the UK’s role in tackling climate change, and explores why there are benefits from taking a lead in reducing emissions.

In December 2015, 194 states and the European Union signed up to the Paris Agreement. This is the most important pact for international cooperation to tackle climate change [1] . By signing the Agreement, the world’s nations have committed to limit the increase in global warming to 'well below 2°C', with a goal to keep it to 1.5°C [2] .

They also set an aim for global emissions to peak as soon as possible, and then achieve a balance between human emissions produced and the removal of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere in the second half on the century; resulting in what is called ‘net zero emissions’. Developed countries have also committed to provide more financial support for developing countries to act on climate change.

By signing the Agreement, countries have committed to submitting and delivering on their own voluntary pledges that set out how they will lower their emissions and adapt to climate change. These are known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The pledges are monitored through an international mechanism that reviews collective progress on the goals of the Agreement. This is the ‘global stocktake’ which will first happen in 2023, and then subsequently every five years.

Countries are legally bound to submit their pledges under the Paris Agreement. Delivering the pledges, however, must be ensured and enforced through national laws and policies. By publicising the different national pledges transparently, the Agreement makes it possible to hold states accountable if they fail to deliver on their promises. The global stocktake mechanism also puts pressure on countries to increase their level of ambition over time, by regularly reviewing progress on the shared global goals.

This approach is part of the reason why international relations experts have suggested that the Paris Agreement was an important new step for global climate change action [3] . By relying on voluntary promises and transparent review processes, it sidesteps the thorny question of how to reach an international agreement on legally binding targets for lowering greenhouse gas emissions. It is hoped that this approach creates a more realistic path for international climate change action [4] .

[1] United Nations Treaty Collection (2015) Paris Agreement . Paris, 12 December.

[2] Falkner, R. (2016). The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics, International Affairs, 92(5), 1107–1125.

[3] Falkner, R. (2016). The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics, International Affairs, 92(5), 1107–1125.

[4] Bodansky, D. (2016). The Paris Climate Change Agreement: A New Hope? The American Journal of International Law, 110(2), 288-319.

The 2015 Paris Agreement committed each of its 195 state signatories to pledge what they will individually do to reduce or limit their greenhouse gas emissions by 2025 or 2030; their so-called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Taken together, however, the current NDCs of all nations are not enough to put the world on track to limit global warming to ‘well below 2°C’[1].

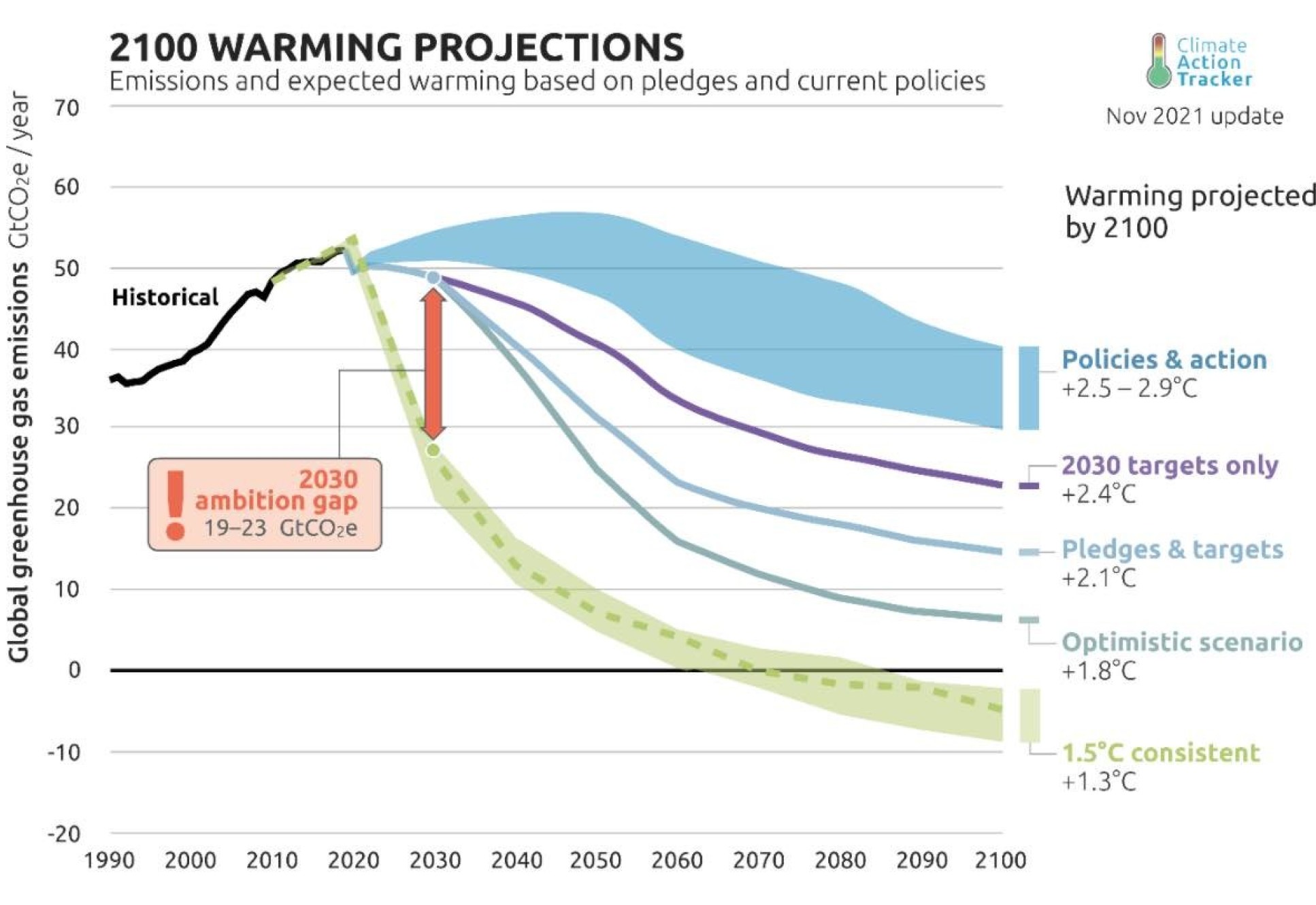

Instead, analysis published by Climate Action Tracker estimates that the current NDC pledges for 2030 are consistent with a global emissions pathway that would lead to a world that is 2.4°C warmer on average at the end of the century, than it was at pre-industrial levels[1]. This is far from being in line with the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit warming to well below 2°C and pursue best efforts to keep it to 1.5°C.

The Paris Agreement explicitly requires each country to revise its pledge and increase its ambition every five years, effectively creating what is called a ‘ratchet mechanism’. Countries agreed at the Paris climate change summit in 2015 to submit revised NDCs by 2021 at the latest, at the 26th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP26) was held in Glasgow, UK, and was postponed from its original date of 2020 due to COVID-19.

Countries were expected to pledge new and more ambitious NDCs ahead of COP26, bringing their actual plans for emissions reductions by 2030 into line with the targets of the Paris Agreement. However, as explained above, countries’ pledges for 2030 still amount to 2.4°C warming. To close this gap, COP26 ended with plans being made for countries to return at COP27 and update their NDC pledges again, rather than wait the originally planned five years.

Steps in the right direction are also being taken by countries that set targets for reaching net-zero emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. Sweden and Norway were some of the first countries to legally commit to net-zero targets, and the UK was the first of the G7 major economies to do so with a commitment to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, closely followed by France. In 2020, China committed to reaching carbon neutrality by 2060, while South Korea and Japan committed to net zero emissions by 2050. Chile and Fiji are also among the countries to have proposed net zero targets, which are pending legislation[2]. Net zero targets have gained increased momentum, and analysts suggest that from November 2021, 90% of global GDP was covered by net zero pledges.[3]

Actually reaching these targets, however, requires rolling out credible policies for reducing emissions immediately. While the UK has set a target for net-zero emissions by 2050, it is currently not set to meet its emission reduction targets for the periods 2023-27 and 2028-2032 respectively. While emissions in the UK power sector have reduced significantly, policies across the rest of the economy are not on track to lower emissions as needed[4].

[1] IPCC. (2018): Summary for Policymakers. In: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V. et al (eds)]. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 32 pp

[2] Wang, H., Lu, X., Deng, Y. et al. (2019). China’s CO2 peak before 2030 implied from characteristics and growth of cities. Nat Sustain 2, 748–754

[3] Gallagher, K.S., Zhang, F., Orvis, R. et al. (2019). Assessing the Policy gaps for achieving China’s climate targets in the Paris Agreement. Nat Commun 10, 1256